Raffia palm (Raphia textilis Wilw) from Hélène Loir's Le Tissage du Raphia au Congo Belge

Raffia palm (Raphia textilis Wilw) from Hélène Loir's Le Tissage du Raphia au Congo Belge

On November 12, Susan Brown, associate curator of fabrics at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, sat down with Conservator Christine Giuntini to go over materials and practices Kongo performers familiar with make the deluxe woven fabrics when you look at the event, open through January 3.

Materials and Dyes

A son extracting the fibrous internal level of hand departs as a primary step up making raffia rope in Bandundu Province, Democratic Republic for the Congo. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Susan Brown: just how is raffia processed to generate fiber?

Christine Giuntini: Raffia materials for weaving tend to be harvested from raffia hand, and there are numerous species. Men rise up the specifically cultivated woods. They stop the closed leaf shoot when it gains a specific level. Next, they isolate the leaflets through the midrib, and employ a knife to remove from the slim green "skin" for each side of the leaflet. The fibers are after that left under the sun to dry. The strands, which are of limited length, tend to be after that more divided manually.

In order to produce the fine, slim strands required for weaving textiles, the fibers must be combed. I understand of just one brush held into the Royal Museum for Central Africa [Tervuren, Belgium]; its unusual to encounter such simple utilitarian items in museum selections. The prepared fibers are after that tied up onto a loom and resources tend to be put into the loom to assist the weaver to keep the fibers when you look at the proper purchase and divide them to the two units.

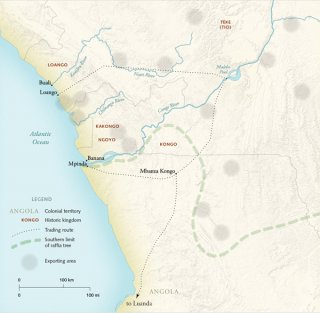

Raffia palms are endemic towards the Kongo region of Central Africa, additionally the high-quality weaving created there was clearly shipped to help south, in which it had been utilized as money. Precolonial raffia circulation and trade channels chart by Anandaroop Roy, according to a map in Jan Vansina's "Raffia Cloth in West-central Africa, 1500–1800"

Susan Brown: The lack of color within human anatomy of tasks are uncommon into the global history of fabrics. You think discover a technical or social basis for the minimal color scheme?

Susan Brown: The lack of color within human anatomy of tasks are uncommon into the global history of fabrics. You think discover a technical or social basis for the minimal color scheme?

Christine Giuntini: In this exhibition, there are only a few raffia pieces to which color has been added. Although the historical sources describe Kongo textiles as brightly colored in shades of red, yellow, and blue, the majority feature their natural color, a deep gold. Your question raises an interesting point, and it is an area for further research.

Susan Brown: that which was regularly produce the additional colors?

Christine Giuntini: While the colors on these particular pieces have not been analyzed scientifically, historical literature indicates that the colors derive from naturally occurring substances such as minerals found in clay or soil, or colorants from plants.

A close-up of a textile shows the also size of the loops of uncut stack raised resistant to the history of ordinary weave. Luxury cloth: cushion cover (detail), 16th–17th century, inventoried 1737. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of Congo; Angola; Republic of this Congo. Raffia; 23 1/4 in. (59 cm) x 23 1/4 in. (59 cm). Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen

We borrowed one textile from Copenhagen's Nationalmuseet specially due to the incomplete condition. It demonstrates how the supplementary weft was raised to create some small loops. Historic sources describe the stack to be formed by small "pins." Its quite feasible that when a row associated with the pile weft was secured into spot because of the warps, the weaver performed use small slivers of lumber to create and keep the small, consistently size loops in place, probably beginning the middle and dealing toward each of the sides.

Susan Brown: just how were different quantities of pattern and texture produced?

Susan Brown: just how were different quantities of pattern and texture produced?

Christine Giuntini: In some of these textiles, ab muscles light-toned weave surrounding the crenellations tend to be entirely voided places where every one of the additional weft is cut right out and you're simply witnessing the building blocks simple weave. The uncut, supplementary weft packages are used to produce a ribbed impact. Uncut packages mirror light differently from the heap. Together the 3 levels give level to the design.

Susan Brown: We clearly see transmission of visual elements from culture to some other, but technology is more entrenched. Performed Kongo weavers ever integrate European materials or other products besides raffia in their weaving?

Christine Giuntini: currently, there is no evidence that any of the surviving sixty-five or so of these presentation cloths and cushions incorporates any product aside from raffia hand dietary fiber.

Shapes and Habits of Kongo Textiles

Depictions associated with diverse forms and uses of woven textiles in Kongo while the nearby kingdom of Loango survive just in pictures. Olfert Dapper (Dutch, 1635–1689). King of Loango (Maloango) engraving from O[lfert] Dapper, Naukeurige Beschrijvinge (Amsterdam), p. 539, 1686. H. 14 9/16 x W. 9 13/16 x D. 2 9/16 in. (37 x 25 x 6.5 cm). Library Gigi Pezzoli, Milan

Susan Brown: Cushion covers, as I understand, were made as diplomatic gift ideas for European dignitaries. Why did the Met focus its choice of pile-woven fabrics on these, and not the blissful luxury cloths that Kongo elites held as a type of wealth?

Christine Giuntini: When the Portuguese first arrived, in 1483, as merchant-explorers looking forward to trade, i really do perhaps not believe they had the mindset of obtaining. Exactly what survived ended up being brought back to European countries during subsequent visits. Following the King of Kongo had declared his Christianity [in 1491], he repaid diplomatic gifts to European princes, possibly in return for gifts sent from European countries. This is why these early works all seem to be presentation pieces [sewn into support format] instead of bits of cloth.

Unfortuitously, nothing survives of opulent Kongo clothing that historical sources explain. Based on familiarity with raffia weaving that existed inside nineteenth century, we think that Kongo artists sewed specific raffia fabric panels collectively to modify garments when it comes to elites.